"It is quite a strange thing to have the species that close to its original habitat," says Carlile. A captive colony was also established on Lord Howe Island in 2009. Melbourne Zoo now has around 1 000 adults and 20 000 eggs. Since the rediscovery of this species, numerous eggs and breeding pairs have been brought to the Australian mainland to breed in captivity. As to how the hefty insects travelled over 20 km of ocean from Lord Howe Island to make Ball's Pyramid their new home, Carlile suspects they floated over as discarded fish bait, or were unwittingly carried by a kind of seabird, called the common noddy, in nesting material.

This little bush, and those that no doubt preceded it, had been sustaining the only Lord Howe Island stick insects in the world for half a century. It turns out this little bush was feeding the entire population of Lord Howe Island stick insects on Ball's Pyramid - 24 individuals in total - providing food and a soft soil surface for them to lay their eggs in. "Even 12, 13 years later it is one of the highlights of my life." Upon revisiting the bush the day after, the team were astounded to find two huge stick insects, quietly straddling the bush. And there sat, as Carlile described it, "a large poo".

Stick ranger pyramid Patch#

Dizzy and dehydrated, they climbed back down to the boat, and passed a single Melaleuca howeana - a dense, short and hardy bush native to Lord Howe Island - that grew in a small crevice containing what was likely to be the only patch of soil on the whole formation. One day, when the conditions were finally calm enough to navigate their little boat through the choppy waters around the edge of Ball's Pyramid, the team climbed about 150 m up the sheer rock face to find a couple of oversized crickets. “David and I decided the only way to mount a trip to Ball’s Pyramid was to take some entomologists, and to prove the things weren’t there,” Carlile says. The team behind the application, Australian scientists David Priddel and Nicholas Carlile from the NSW Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water ranger Dean Hiscox entomologist Stephen Fellenberg and entomology curator Margaret Humphrey from the Macleay Museum at the University of Sydney, travelled to Ball's Pyramid in 2001 to prove, once and ford all, that the Lord Howe Island stick insect was extinct. It took over ten years for a successful application to be made, and the proposal certainly wasn't to find the big, black trophy many explorers had tried to locate on Ball's Pyramid before the ban. It not only sounds hellishly difficult to explore - there's barely anywhere flat to stand on it - in 1984, the Lord Howe Island Board made it illegal for anyone to climb it except specifically for scientific work. They were rumoured, however, to be living in on Ball’s Pyramid, a super-sheer volcanic stack about 20 km from Lord Howe Island, which measures around 550 metres high, 300-metres wide and one-kilometre-long. Twelve other invertebrate species and five bird species were also driven to extinction because of the rats. Soon, sightings of the Lord Howe Island stick insect declined to such an extent that by 1920, not a single one was found, and by 1960, they were declared extinct.

Makambo in 1918, which led to the decimation of the endemic stick insect population.

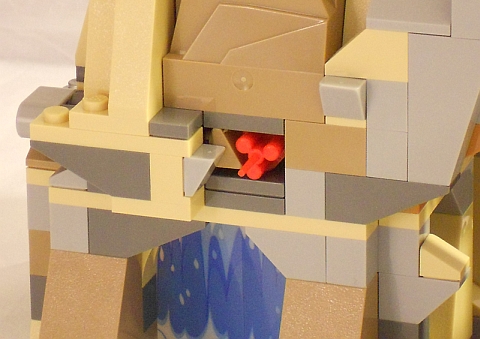

Then mice were introduced to the island in the 1880s, and black rats hitched a ride on the British vessel S.S. So common were these insects, that fishermen would use them as bait and their wives would dread running into one on a trip to the outback toilet. In the 19th century, the Lord Howe Island stick insect ( Dryococelus australis) was a common site on its native Lord Howe Island, which is located about 700 km east of Port Macquarie in New South Wales. It will grow up to be a flightless, nocturnal insect that stretches up to 12 cm long, its solid, shiny black or rust-coloured body weighing up to 25 grams. That chartreuse green insect is unfurling from its little egg to add to a slowly swelling captive population of Lord Howe Island stick insects - one of the rarest, and largest, insects in the world - at Melbourne Zoo. This wonderful photograph, which was one of the ten highly commended entrants in the 2012 New Scientist Eureka Prize for Science Photography, captures an extremely special event.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)